Pre-Enlightenment Philosophy in Scotland

Stair's Pre-enlightenment Philosophy ... Before the Universities

The earliest major contributer to pre-enlightenment philosophy with a clear Scottish connection was Duns Scotus– not a name, but a description “the Scot from Duns”. Not much is known of his life. He was born probably around 1266 at Duns, today a small town of about 2500 people situated close to the border between Scotland and England. This may be his only substantial connection with Scotland, in fact, since he was ordained priest in England, and was educated at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Paris. He began lecturing at the prestigious University of Paris in the Autumn of 1302, but not long after was expelled – the victim of church politics. He returned there in 1304, and about three years later he was sent to the Franciscan college at Cologne, where he died in 1308.

Known as "Doctor Subtilis" because of the subtle distinctions he employs, Scotus is considered one of the most important Franciscan theologians. Although he gave his name to a special form of Scholasticism – ‘Scotism’ – this cannot in any serious sense be considered a distinctively Scottish school of thought. Generally considered a metaphysical ‘realist’, Scotus held that universal terms are not merely classificatory names, but identify kinds of things that share a real common nature. Realism in this sense was widely endorsed by later Scottish philosophers, but philosophy at the time of Scotus was a European enterprise, closely tied up with Christian theology. None of its exponents can properly be identified with distinguishable national cultures, which barely existed in the pre-enlightenment period.

The Ancient Universities of Scotland

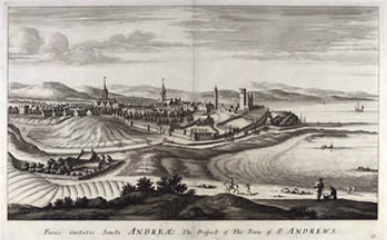

Like every other Scot seeking an education, Scotus had to travel to Cambridge, Oxford and Paris because there were no universities in Scotland. This changed early in the 15th century when between 1411 and 1413 the University of St Andrews was founded. Forty years later, in 1451, a second university was established at Glasgow, followed by a third at Aberdeen in 1495. All were pre-reformation church institutions founded by Papal authority. In the next century, two Protestant universities were established. The Town Council of Edinburgh, with the authority of the Crown, established a new ‘College' in 1582 and at Aberdeen a second ‘College' named after the Earl Marsichal, came into existence in 1593. All these foundations survived to become major contemporary universities, the two university colleges at Aberdeen having been united in 1860. One initiative failed, however. The entrepreneur Sir Alexander Fraser (1537-1623), 7th Laird of Philorth in Aberdeenshire, founded the harbour town of Fraserburgh in 1576 and in 1592 he established a University of Fraserburgh there – Scotland's sixth. But five years later lack of funds led to its collapse. Beginning with the appointment of the philosopher Laurence of Lindores as first Rector at St Andrews, Hector Boece at Aberdeen and extending to the two later Protestant foundations, all these universities included well educated philosophers among their founding scholars and gave special emphasis to the teaching and learning of philosophy. From an early stage they both produced, and subsequently gave employment to, almost all the best known Scottish philosophers (David Hume, who never held a university post, being the most striking exception). It is this educational base, its development and social influence over several centuries, that gave the Scottish philosophical tradition its identity and continuity, and that enables us to speak of such a tradition at all.

Medieval logic

Amongst the earliest philosophers who have a clear institutional connection with Scotland, two names stand out – John Mair (or Major) and George Lokert. Mair studied and taught in Paris, where he has been described the ‘leader of Scottish intellectual life', and Lokert was one of his circle. Born in East Lothian around 1467, it is only conjecture that Mair studied at the relatively new University of St Andrews, Cambridge and Paris being his recorded places of education. But he subsequently spent a considerable part of his academic life in Scotland, first as Principal of the University of Glasgow, and then as Rector of St Andrews where he taught both Arts and Theology. Mair was a prolific writer in his own right, but also led a ‘team' of philosophical logicians and scholarly editors whose academic work was outstanding.

Lokert followed a path similar to Mair's. Born in Ayrshire sometime around 1485, he was a student and teacher at Paris, and subsequently Rector of St Andrews, eventually returning to Paris. He wrote very extensively on logic, and was responsible for revising the examination procedures at St Andrews to bring them into line with Continental standards.

Calvinism and the Reformation

Among Mair's students at St Andrews was John Knox (1513?-72), the most famous of Scotland's Protestant reformers. Knox's theological and political writings were strongly influenced by Jean Calvin's Geneva, and in combination with the Renaissance humanism of George Buchanan, this led to curricular reforms at Glasgow, St. Andrews and Aberdeen, as well as shaping the curriculum favored by first principal of the new University of Edinburgh. In part these changes signalled a move towards theology and away from philosophy since they included the abandonment of Aristotelian logic, the elimination of metaphysics, and the use of a much wider range of classical texts in ethics. Philosophy nonetheless continued to be a foundational subject in arts, and regarded as an essential preliminary to the study of theology. Towards the end of the 17th century a philosophical renaissance of sorts began in which three figures stand out, all of them teachers of philosophy at Glasgow. James Dalrymple (1619-95), later Viscount Stair, is best known for his authorship of the Institutes of the Law of Scotland (1681). The Institutes had a wide and enduring influence on the character of Scots law as based on principles rather than cases, and the work reveals the important influence of the period Stair spent as a student and teacher of philosophy before his move to the law. Stair's student and successor, Hugh Binning (1627-53) was primarily interested in theology, but again his published works show the influence of philosophical thinking, particularly on ethical and social issues. This continuing engagement with philosophy finally combined with Calvin's moral, economic and political thinking in the form of a ‘Protestant' version of natural rights theories. Developed by Hugo Grotius and especially Samuel Pufendorf, it provided the foundation for a restoration of moral philosophy at the hands of Gershom Carmichael (1672-1729) whose interests, publications and students form the bridge between Calvinism and the Enlightenment.